Dyre Malware Analysis

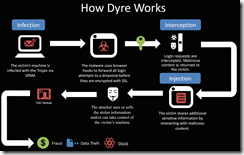

Dyre, also known as Dyreza, is a banking Trojan that was first seen around June 2014. With the combination of its ability to steal login credentials by browser hooking and bypassing SSL, its man-in-the-middle (MITM) proxy server, and its Remote Access Trojan (RAT) capabilities, Dyre has become one of the most dangerous banking Trojans. The Dyre Trojan is designed to steal login credentials by grabbing the whole HTTPS POST packet, which contains the login credentials sent to a server during the authentication process, and forwarding it to its own server. The malware downloads a configuration file containing a list of targeted bank URLs. Each URL is configured to be redirected to Dyre’s MITM proxy server, on a different port for each bank. This allows the attacker to make a MITM attack by forwarding any user request to the bank and returning bogus data, including fake login pages, popup windows, and JavaScript/HTML injections. After all the information has been acquired by the attacker, he can remotely access the victim’s computer using a built-in VNC (Virtual Network Computing) module and perform transactions, data exfiltration, and more. How it works malware downloads a configuration file containing a list of targeted bank URLs. Each URL is configured to be redirected to Dyre’s MITM proxy server, on a different port for each bank. This allows the attacker to make a MITM attack by forwarding any user request to the bank and returning bogus data, including fake login pages, popup Malware behavior on a Win7-32bit system Surprisingly, the malware behaves differently on Win7-32bit, most likely due to security implementation differences. The method of registering itself as a system service is implemented on WinXP and 64bit systems (tested on Win7-64bit). On Win7-32bit, Dyre operates more similarly to the known Zeus malware by injecting code in the Explorer.exe process and operating from there. Man-In-The-Middle (MITM) Attack When a user enters his bank’s URL in the browser line, the Trojan is triggered and forwards the URL to the corresponding proxy server as stated in its configuration file. · The MITM proxy server forwards requests to the banks and disguises itself as the real user. · The returning response from the bank is intercepted by the proxy server. · Instead of the real response, the user receives a fake login page which is stored on the proxy server, and contains scripts and resources from the real bank’s page. The scripts and resources are stored in folders named after the unique port configured for each bank. · The information entered by the user is sent to the proxy server and then forwarded to the real bank server, allowing the attacker to log in instead of the user and perform operations on his behalf. The fake login page The fake page contains a script called main_new - , which is responsible for handling the objects presented to the user on the fake page and performing the MITM attack. The fake page contains an array of configuration parameters in the header. Some of the more interesting ones are: · ID. The unique identification of the bank, which is the same as the port number in the configuration file. · Incorrect login error. On each login attempt to the bank, the proxy server will forward the request to the real bank’s server and perform the authentication. If the authentication fails, it will also present an error to the user on the fake page. · Block message. If the MITM attack succeeds, the attacker is able to perform a transaction and block the user from accessing his account. This parameter stores the presented message. The F5 Solution Real-time identification of affected users - F5 WebSafe and MobileSafe are able to detect the user is affected by a Trojan and that the information provided by it to the customer is also sent to an unauthorized drop zone. Identification of malicious script injection – once downloaded to the client’s browser, WebSafe and MobileSafe make sure there has been no change to the site’s HTML. If such a change is detected, the customer is notified immediately. Protection against Trojan-generated money transfers - the combination of recognizing affected users, encrypting information, and recognizing malicious scripts is key to disabling Trojans from performing unauthorized actions within the account. WebSafe and MobileSafe detect the automatic attempts and intercept them. Malware research - F5 has a dedicated Trojan and malware R&D team that searches for new threats and new versions of existing ones. The team analyzes the programming techniques and methodologies used to develop the malware in order to keep the F5 line of products up to date and effective against any threat. To get the full technical detailed Malware analysis report click here. To download the executive summary, click here.1.4KViews0likes2CommentsMalware Analysis Report: Cridex Cross-device Online Banking Trojan

Co-Authored with Itzik Chimino. --- The F5 Security Operation Center In 2013, F5 Networks acquired the security company Versafe, the developer of an online banking anti-fraud solution that fit neatly into F5’s security story. An additional asset gained from the acquisition was the Versafe security operations center (SOC). The SOC works with customers and end-users to analyze malicious software, from which it publishes periodic threat intelligence based on those analyses. The SOC report for January 2014 provides an analysis of a variant of the Cridex cross-device malware, which has been observed attacking online banking customers in 2013. This malware variant exhibits several alarming attributes, including: Ability to attack dozens of retail bank sites Transmission via spear phishing Malicious script injection Ability to bypass two-factor authentication (2FA) via a mobile malware component Bogus use of vendor’s endpoint security software as the lure for the malware The significance of these attributes signals a new baseline of malware sophistication. Analysis Highlights The January report shows each of the variant’s attack characteristics by examining the flow of the attack, starting with spear-phishing and culminating with an automated financial transaction that steals the victim’s money. Spear Phishing The attack begins with a broad message campaign. Because this variant can attack so many different retail banking sites, the campaign does not need to be targeted at a particular set of banking customers. The messages can be SMS texts, emails or Facebook messages. The report includes a sample of an email that appears to originate from Facebook, tricking the user into clicking a link. Malicious Script Injections The user believes that clicking the link will show social notifications, but in reality, he is directed to a website that probes his browser for vulnerabilities through which the website can install the Cridex desktop malware variant. After infection, when the user connects to his banking website, the variant malware selects the malicious code designed specifically for that bank and injects it into the user’s browser. Ultimately, the injected script will attempt a money transfer. The variant of the Cridex malware analyzed in the report also records the end user’s banking credentials (the username and password) and sends him to an offsite “drop zone.” Bypassing Two-Factor authentication Malware that steals banking credentials has been a known problem for years. One of the most effective countermeasures that the banking industry has put in place is two-factor authentication (2FA). This means that the user must authenticate not only via password but with an additional, non-guessable piece of information. Most online banking institutions use SMS (texting) for this – they will transmit a six character code via text to the user’s mobile device. The user then inputs that code as the second element of their authentication information. According to the January SOC report, the variant of Cridex can bypass this SMS-based 2FA countermeasure. Mobile Malware masquerading as endpoint security The bypass works by installing additional malware onto the user’s mobile device. In one example cited by the report, the malware variant in the user’s browser fakes an alert that the bank is now asking all users to install an endpoint security software solution on mobile devices to prevent fraud. The unsuspecting end user, wanting to do the right thing, installs the mobile malware which impersonates security software. After the mobile malware is installed, it monitors incoming texts for the 2FA code sent by the bank. It intercepts these and sends them to the dropzone, where they are retrieved by the malware running in the user’s browser to complete an automated transaction. Conclusion and Publication Malware sophisticated enough to have a specific attack scripts for dozens of different online banks poses a significant threat to the global retail banking industry. The fact that it is already capable of bypassing two-factor authentication via SMS makes it an even more urgent issue to address. The January 2014 SOC malware analysis report contains the full breakdown of this variant of the Cridex malware and provides guidance on how it, and other variants, can be impeded. The January 2014 Security Operation Center report can be downloaded here.541Views0likes0CommentsDomain name holders hit with personalized, malware-laden suspension notices

This according to Zeljka Zorz, HNS Managing Editor from Help Net Security. In his article, Zeljka mention that new email spam campaign has been spotted targeting domain name holders, trying to trick them into downloading malware on their systems. The email is likely to fool some recipients, as it contains the valid domain registration and the recipient's full name, which the attackers must have harvested online, via the “whois” query. The sender's email address is also spoofed to make it look like the sender is the domain registrar. Those who get fooled and download and execute the file linked in the email will get saddled with malware - most likely a Trojan downloader, which will then proceed to download additional malware. Below is the spam e-mail that was sent: Subject: [Domain name] Suspension Notice Dear Sir/Madam, The following domain names have been suspended for violation of the Melbourne IT Ltd Abuse Policy: Domain Name: [domain name] Registrar: Melbourne IT Ltd Registrant Name: [Registrant name matching whois] Multiple warnings were sent by Melbourne IT Ltd Spam and Abuse Department to give you an opportunity to address the complaints we have received. We did not receive a reply from you to these email warnings so we then attempted to contact you via telephone. We had no choice but to suspend your domain name when you did not respond to our attempts to contact you. Click here [LINK] and download a copy of complaints we have received. Please contact us by email at mailto:abuse@melbourneit.com.au for additional information regarding this notification. Sincerely, Melbourne IT Ltd Spam and Abuse Department Abuse Department Hotline: 480-124-0101 According to the article, the most targeted registrars are Melbourne IT and Dynadot that already notified their clients of this campaign. In their official notification Dynadot states that “We have recently become aware of fake abuse notifications being sent out to our customers. The abuse messages look like they are being sent from our abuse@dynadot.com email; however, these messages are NOT being sent from us and should be disregarded. If you receive one of these emails or an email that you think may not be from us, do not click on any links, reply directly to the email, or call the number listed in the email". To read Melbourne IT public announcement click here. F5 SOC is familiar with this spam campaign as well with many others that come and go almost every day. This attack vector is very common in the hacktivists communities that using Social Engineering to lure victims into opening links and/or attachments in e-mail messages in order to broader their botnet pools and inititate DDoS attacks, money transfer, identity theft and more. On a day to day basis, F5 mitigates online identity theft by preventing phishing, malware, and pharming attacks in real time with advanced encryption and identification mechanisms enabling financial organizations working online to gain control over areas that were once virtually unreachable and indefensible, and to neutralize local threats found on customers’ personal computers, without requiring the installation of software on the end user side. If you would like to learn more about F5 fraud protection, read the WebSafe datasheet as well as the MobileSafe datasheet. To learn more about F5 Security Operation Centers, read the F5 SOC datasheet. Click here to read the original article by Help Net Security.484Views0likes0CommentsiBanking Malware Analysis

Co-Authored with Itzik Chimino. --- iBanking is malware that runs on Android mobile devices. It is delivered via a new variant of the computer banking Trojan Qadars, which deceives users into downloading iBanking malware on to their android device. It can be used with any malware used to inject code into a web app. The malware enables cybercriminals to intercept SMS and bypass the two-factor authentication methods used by several banks throughout the world to authorize mobile banking operations. iBanking malware acts as a spy that can also of grab contact lists, steal bank account details, forward incoming voice calls, and record the victim’s voice, which enables it to overcome voice recognition security features that financial institutions are beginning to implement. Cyber criminals ultimately utilize iBanking malware to transparently complete money transfers on behalf of the infected targeted users. How the attack works Focusing specifically on the new variant of iBanking malware that targets Facebook users, the attack begins by infecting users’ devices with the Qadars banking Trojan via a drive-by download from an unsuspecting website. Qadars then intercepts the webpage and uses JavaScript to inject code into the webpage—in this case, a Facebook page—that presents users with a fake verification pop-up page upon initial login. This page requests the victim’s phone number and Android device confirmation. The victim then receives an SMS message on the verified device, which directs him to a page with instructions to download added security. Once the victim installs the iBanking malware, it cannot be removed if it was given admin rights during the install process. Remote control of the infected device Once the malware is activated by the user on his smartphone, the attacker gains administrator permissions on his device. The attacker can now control a vast amount of functions such as: 1. Allows applications to change network connectivity state. 2. Allows an application to send/read SMS messages. 3. Allows an application to automatically start when the system boots. 4. Allows an application read-only access to phone state. 5. Allows an application to access approximate location derived from network location sources such as WiFi and cell antennas. 6. Allows an application to initiate a phone call without going through the Dialer user interface for the user to confirm the call being placed. 7. Allows an application to open network sockets. 8. Allows an application to write to external storage such as modify/delete SD card contents. 9. Allows an application to read the user's contacts data. 10. Allows an application to record audio such as phone calls and voice messages. Click here to read the full technical iBanking Malware Analysis Report by F5 SOC. To read more about F5 Global Security Operation Centers click here.429Views0likes3CommentsA New Twist on DNS NXDOMAIN DDoS

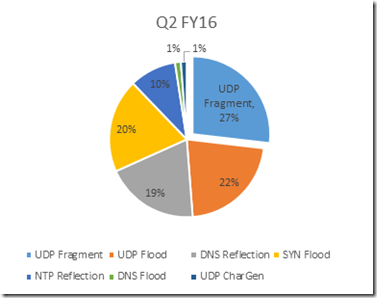

DDoS attacks are increasing in scale and complexity, threatening to overwhelm the internal resources of businesses around the world. The F5 Silverline Security Operations Center (SOC) recently saw a new distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attack vector targeting a customer’s DNS servers with malicious traffic averaging between 8 and 12 Mbps and bursts of malicious traffic peaking at over 100 Mbps. This attack began in mid-August and continued through November 2015. It was not a typical reflection attack where DNS servers are used to attack a web site, but an attack against the actual DNS servers. Through additional investigation, the SOC analysts identified the vector and crafted a targeted mitigation for this new “_dmarc” attack. In their investigation, Edgar Ojeda and his colleagues found that F5 Silverline customer's DNS servers were receiving hundreds of thousands of randomized queries for “_dmarc” DNS records even if from a volumetric standpoint this amount of traffic seems to be trivial. Then, they noticed that _dmarc DNS queries were for non-existent subdomains and that customer’s DNS infrastructure was becoming unstable. As the attack continued and after further investigation, F5 SOC created a finely tuned signature that successfully scrubbed all malicious traffic and the customer’s service became operational again. To read the full report describing the attack, click here. If you are under attack, just click this link and we can get you back online! Click here to learn more about howF5 Silverline mitigate DDoS attack.394Views0likes0CommentsSlave Malware Analysis

During the last couple of weeks, Nathan Jester, Elman Reyes, Julia Karpin and Pavel Asinovsky got together to investigate the new “Slave” banking Trojan. According to their research, the early version of the Slave performed IBAN swapping in two steps with great resemblance to the Zeus “man-in-the-browser” mechanism. First, the host header is compared to a hard-coded bank name. If the match is successful, the hard-coded HTML tag is searched throughout the request body and the content is swapped if it matches the IBAN pattern. Then, After the browser infection which takes place in the exact manner as the later version, the malware places hooks on the outbound traffic functions. The latest version of the Slave is, of course, much more sophisticated than the first one and include creation of registry keys with random names, IE, Firefox and Chrome infections, kernel32.dll hooks and more. However, one of the most interesting capabilities of the Slave is the timestamp check. As can be seen in the screenshot below, the malware is conditioned to run before April 2015 and not after that so the sample is basically "valid" for two weeks only, probably to avoid research and detection. Click here to download the full technical Malware Analysis Report. Or here for the Executive Summay Report. To learn more about F5 Security Operation Centers, visit our webpage. -- Editors Note: F5 and DevCentral do not condone the usage of the term ‘slave’ in the context of our technology. In this case the term ‘slave’ is a name, used to specify a particular piece of malware. We believe removing or changing the term, here, would only cause confusion and remove information necessary for effective application security.361Views0likes0CommentsDyre presents server-side web injects

Dyre is a relatively new banking Trojan, first seen in the beginning of 2014. It soon emerged as one of the most sophisticated banking and commercial malware in the wild. One of the main capabilities Dyre has presented, which differentiated it from the other well-known banking Trojans, was the “fake bank page” functionality. Once the victim tries to reach the real bank, Dyre intercepts the request and fetches its own fake page from one of its C&C servers. However, while researching the Trojans’ internals we noticed another stage in the fraud techniques evolution. “Traditional” fraud malware performs malicious JavaScript injection on the client machine while taking it from a configuration previously downloaded from the C&C server. However, Dyre maintains the injections on its C&C servers. This gives Dyre the flexibility to adjust the injected code on demand and minimize exposure of the existing web-injects. During our research we noticed two types of injections which lead to two different scenarios. In the first scenario, the web-injects (malicious JavaScript) stole just the login credentials, while in the second scenario it would also contain an embedded HTML page which targets credit card information as well. Other than just targeting financial online applications, using the “Grabber” module, Dyre enables its operators to steal virtually any user-supplied sensitive information online in large amounts. This information includes credentials for email applications, social platforms, hosting infrastructure, and corporate SSL-VPNs. While this information may be resold in the “underground”, the bigger risk is that malware operators might hijack email and social network accounts to perform surveillance, or blackmail individuals or organizations. They could also hijack hosting infrastructure to further deploy other malicious code, or break into organizations using stolen VPN credentials. Many have written about this new threat. However, few have succeeded in covering the entire fraud flow and most of its capabilities. For more details on the Trojan’s internals, read the report: https://devcentral.f5.com/s/d/dyre-malware-internals?download=true339Views0likes0CommentsF5 SOC Malware Summary Report: Neverquest

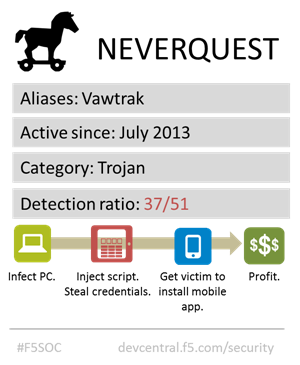

#F5SOC #malware #2FA #infosec The good news is that compromising #2FA requires twice the work. The bad news? Malware can do it. That malware is a serious problem, particularly for organizations that deal with money, is no surprise. Malware is one of the primary tools used by fraudsters to commit, well, fraud. In 2013, the number of cyberattacks involving malware designed to steal financial data rose by 27.6% to reach 28.4 million according to noted security experts at Kaspersky. Organizations felt the result; 36% of financial institutions admit to experiencing ACH/wire fraud (2013 Faces of Fraud Survey). To protect against automated transactions originating from infected devices, organizations often employ two-factor authentication (2FA) that leverages OTP (one time passwords) or TAN (transaction authorization numbers) via a secondary channel such as SMS to (more) confidently verify identity. 2FA systems that use a secondary channel (a device separate from the system on which the transaction is initiated) are more secure, naturally, than those that transmit the second factor over a channel that can be used from the initiating system, a la an e-mail. While 2FA that use two disparate systems are, in fact, more secure, they are not foolproof, as malware like Neverquest has shown. Neverquest activity has been seen actively in the wild, meaning despite the need to compromise two client devices - usually a PC/laptop and a smartphone - it has been successful at manipulating victims into doing so. The primary infection occurs via the PC, which is a lot less difficult these days thanks to the prevalence of infected sites. But the secondary infection requires the victim to knowingly install an app on their phone, which means convincing them they should do so. This is where script injection comes in handy. Malware of this ilk modify the web app by injecting a script that changes the behavior and/or look of the page. Even the most savvy browsers are unlikely to be aware of such changes as they occur "under the hood" at the real, official site. Nothing about the URI or host changes, which means all appears as normal. The only way to detect such injections is to have prior knowledge of what the page should look like - down to the code level. The trust a victim has for the banking site is later exploited with a popup indicating they should provide their phone number and download an app. As it appears to be a valid request coming from their financial institution, victims may very well be tricked into doing so. And then Neverquest has what it needs - access to SMS messages over which OTP and/or TAN are transmitted. The attacker can then initiate automated transactions and confirm them by intercepting the SMS messages. Voila. Fraud complete. We (as in the corporate We) rely on our F5 SOC (Security Operations Center) team to analyze malware to understand how they compromise systems and enable miscreants to carry out their fraudulent goals. In July, the F5 SOC completed its analysis of Neverquest and has made its detailed results available. You can download the full technical analysis here on DevCentral. We've also made available a summary analysis that provides an overview of the malware, how it works, and how its risk can be mitigated. You can get that summary here on DevCentral as well. The F5 SOC will continue to diligently research, analyze and document malware in support of our security efforts and as a service to the broader community. We hope you find it useful and informative, and look forward to sharing more analysis in the future. You can get the summary analysis here, and the full technical analysis here. Additional Resources: F5 SOC on DevCentral F5 WebSafe Service F5 Web Fraud Protection Reference Architecture314Views0likes0CommentsIs Slempo/GM-Bot the new standard for mobile malware?

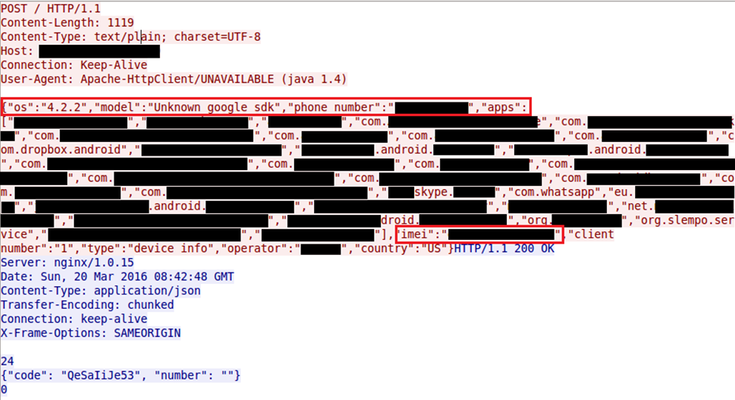

Introduction Slempo/GM-Bot requires little introduction, as it has been the focal point of many recent publications, and is a well known threat in the world of mobile malware. In most cases Slempo/GM-bot presents itself as “Adobe Flash Player Update”, this disguise is very popular in the mobile malware sphere, and used in order to trick the user into granting the malicious application administrator privileges. Upon the user’s acceptance the malware is installed on the device and is capable of controlling it. Among the malware’s many functionalities are: Intercept, redirect and block SMS messages and calls Lock and unlock the device Wipe the device Display it’s own content over legitimate applications Send stolen user credentials (obtained by displaying fake content) back to the Command & Control server. After completing initial installation, the malware will contact its Command & Control server, send it a list of all applications installed on the device and various other device information, and will download a configuration file which it will save locally on the device at the following path: /data/data/%App_Name%/shared_prefs/AppPrefs.xml This configuration file contains the applications that the malware targets for credential harvesting, and the fraudulent content that performs that harvesting. Fig. 1 – Device data and installed applications sent to C&C server. Encoded Configuration & Fraudulent Activity The encoded configuration file which is downloaded from the Command & Control server contains the targeted application names and content to be displayed to the victim upon activation of a targeted application, as can be seen below: Fig. 2 – A snippet of the encoded configuration file Fig. 3 – Decoded configuration snippet showing fraudulent HTML content to be displayed on top of the targeted application and harvest user’s credentials. When the malware detects activation of a targeted application, the fraudulent content contained in the configuration file is displayed to the victim on-top of the targeted application: Fig. 4 – Fraudulent content displayed on top of legitimate application. After entering his credentials into what the victim perceives to be the legitimate application, the malware then sends the credentials to its C&C server, as seen below: Fig. 5: Victim’s credentials are sent to the C&C server. Targets Slempo targets many various financial and non-financial applications worldwide, as can be seen in the chart below: Fig. 5: Slempo Target Distribution. NOTE: Applications which are not region or country specific are categorized as “Other”. Known Slempo/GM-bot Sample MD5s: 288ad03cc9788c0855d446e34c7284ea e740233e0a72be4db2dcd5d5b7975fa0 3ef8e4ea08e9eff6db3c9ebf247a97b5 45e66a89db86309673d33b1aa4047fd1 a5387f3487c0749394def743a7345c47 f90cded5ec2a6c29b636945af85e3069 Mitigation To learn more about F5 fraud protection and how F5 can mitigate threats such as Slempo, please read the MobileSafe datasheet as well as the WebSafe datasheet.276Views0likes0CommentsTinba Malware – New, Improved, Persistent

As investigated by Pavel Asinovsky, F5 SOC Malware Researcher, Tinba, also known as “Tinybanker”, “Zusy” and “HµNT€R$”, is a banking Trojan that was first seen in the wild around May 2012. Its source code was leaked in July 2014. Cybercriminals customized the leaked code and created an even more sophisticated piece of malware that is being used to attack a large number of popular banking websites around the world. The original Tinba malware was written in the assembly programming language and was noted for its very small size (around 20 KB including all Webinjects and configuration). The malware mostly uses four system libraries during runtime: ntdll.dll, advapi32.dll, ws2_32.dll, and user32.dll. Its main functionality is hooking all the browsers on the infected machine, so it can intercept HTTP requests and perform web injections. The new and improved version contains a domain generation algorithm (DGA), which makes the malware much more persistent and gives it the ability to come back to life even after a command and control (C&C) server is taken down. Tinba configuration file reveals browser injections of several targeted banks, mainly from Australia, but also from Germany, Spain, Finland, and Switzerland. There are multiple injection types, most likely bought in the underground from different Webinject writers. There is a generic VBV grabber, ATSEngine CC+VBV grabber, some specially crafted injections that are adjusted to each bank, and some other miscellaneous injections such as a Bitcoin stealer. Some of the man-in-the-browser (MITB) panels and files are hosted on different servers. The ATSEngine CC+VBV grabber is also widely used by the known Zeus Trojan, and is sold as a toolkit in the underground. This is a dynamic injection that can be updated easily on the server side without sending a new configuration to each bot, and it can be configured to steal credit card and other sensitive information from Google, Yahoo!, Windows Live, and Twitter websites. When an infected user logs in to his banking account, a specially crafted injection may produce a popup requesting additional details, credit card information, PIN/OTP authentication, or other info that may be used for fraudulent activities such as performing transactions, stealing sensitive data, and more. It all depends on the configuration of the malware and the script it injects. Some scripts may present false information in regards to the banking account, such as balance information, history of transactions, out-of-service messages, and more. Download Tinba full technical analysis report from here. Get your Tinba executive summary here.275Views0likes0Comments